The use of Spanglish in the American classroom has not only become common practice but is also proving itself to be a useful tool, especially in classes with younger students. School populations are becoming more and more diverse, and creating the best possible learning environments for all students in bilingual classrooms is immensely important. Not only is Spanglish proving itself to be beneficial for children, but also for teachers who, at any moment, may have to switch back and forth between different languages in response to the students present or even the classroom environment. These kinds of situations as well as a teacher's performance in handling them were documented by researchers and authors Kathryn Henderson and Mitch Ingram.

To ensure Spanglish is being presented to students in an effective way, the proper tools must be utilized to ensure students become both interested and encouraged in viewing Spanglish as an acceptable means of communication.

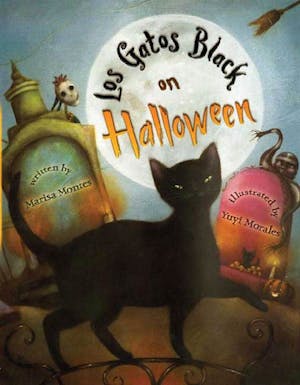

With the language's growth and ever-increasing visibility in recent years, children's picture books containing elements of or being written fully in Spanglish have increased greatly. One that utilizes Spanglish effectively and incorporates Hispanic culture is Los Gatos Black on Halloween by Marisa Montes and Yuyi Morales. The story following the activities of children's favorite Halloween creatures will grab the attention of younger students, meanwhile the darker art depicting scenes influenced by Dia De Los Muertos will attract older students as well.

It is also important to remember, however, that for as many supporters of Spanglish there are, so too exist just as many detractors. If teachers are willing to incorporate Spanglish in their classrooms, they have to be aware of potential risks. Authors Sharon Chappell and Christian Faltis have done a deep dive into several Spanglish children's books and found that many contain potentially harmful messages aimed at kids, like the notion that they are betraying their cultures by adopting Spanglish over their native language.

Spanglish has only gained popularity and visibility in recent years, and for teachers to truly be able to create comfortable and effective learning spaces for diverse classrooms, the implementation of Spanglish is becoming necessary in schools.